The 1960s Output of Coltrane, Davis and Hancock.

By Brian L. Knight

Since its inception, jazz has been a continuously evolving art form. Since its pre-World War I Dixieland days right up to Kenny G’s Grammies, jazz has never been typified by stasis. After World War II, the transformation of jazz became an exponential event in which the art form went from swing, bebop, hard bop, soul-jazz, avant-garde, freebop, fusion, jazz-funk, contemporary and smooth. The 1960s was a perhaps the most transitional decade for jazz and the music industry as a whole. Rock & roll was becoming the dominant musical force as kids were flocking to the concert halls and the British invasion, led by the Beatles, was the worldwide rave. In jazz, the funky soul-jazz sounds were taking over the mainstream and the blistering chaotic compositions of the avant-garde were enjoying a brief window of popularity. Despite a continuous output of quality jazz music, the genre had tremendous difficulties standing up against the growing rock & roll surge. As record companies focussed their A & R Departments on signing new rock and roll bands, jazz was deemed as a has been. This relative demise eventually led to a gradual transformation of jazz into fusion, funk and ultimately, contemporary smooth jazz. Pianists plugged their pianos in, bandleaders recruited electric guitarists and trumpets and saxophones became electrified. Before the total onslaught of the music revolution of the late 1960s, there was a window during the early/mid 1960s where modern jazz remained true to its acoustic and compositional roots, yet displayed incredible innovation and musical evolution. This mid 1960s period of creativity was led Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Herbie Hancock.

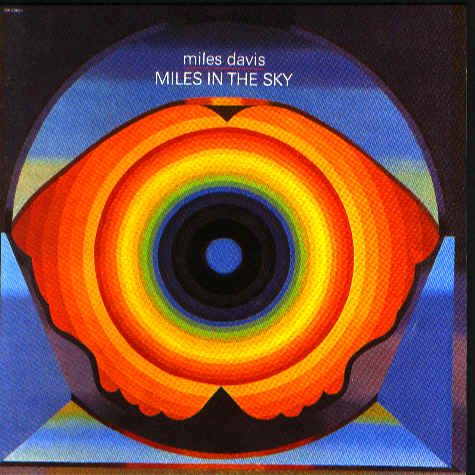

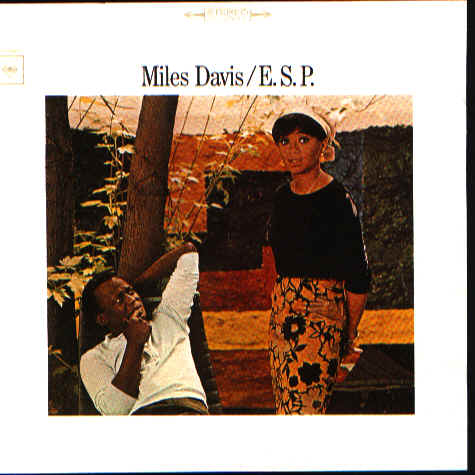

To celebrate the work of these three great artists during this period, there has been a slew of box sets that provide ample samplings of these artists' most profound and ethereal work. A few years back, Columbia/Legacy released The Miles Davis Quintet, 1965 –1968: The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings. This 6 CD compilation provided 56 tracks of music that came from the music of his second great quintet, which featured Davis, Tony Williams(drums), Ron Carter(bass), Herbie Hancock(piano) and Wayne Shorter(saxophone). To complement this box set, the individual albums (E.S.P., Sorcerer, Miles Smiles, Miles in the Sky and Nefertiti) from this period have been re-released with bonus tracks. Almost a direct reflection of the Davis box set, Impulse released Coltrane: The Classic Quartet- Complete Studio Recordings, which covers the master saxophonist work from 1961 to 1965. During these years, Coltrane played with the relatively steady quartet of McCoy Tyner(piano), Elvin Jones(drums) and Jimmy Garrison(bass) and recorded classic albums such as Coltrane, Ballads, Impressions, A Love Supreme, Meditations and Sun Ship. While Herbie Hancock can not boast a classic quintet or quartet, he can easily lay claim to fame to some spectacular albums such as Takin' Off, Inventions and Dimensions, Empyrean Islands, Maiden Voyage and The Prisoner. To celebrate these sessions, Blue Note Records released Herbie Hancock: The Complete Blue Note Sixties Sessions, a six CD set featuring tracks from these albums, bonus tracks from these sessions and tracks featuring Hancock’s on other musicians albums. The bonding agent for all of these releases would have to be Miles Davis. Before John Coltrane’s astonishing sessions with Impulse as a leader, he was playing with the Miles Davis’s first great quintet as well as his famous sextet and during the years of the second great quintet, Herbie Hancock was the primary pianist for Davis.

John Coltrane spent the late 1950s in and out of Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk’s bands. Coltrane’s tenure with Miles Davis was known as Miles Davis First great quintet. Along with Red Garland, Philly Joe Jones, Paul Chambers, Coltrane and Davis recorded classic bop albums such as Relaxin’, Cookin’, and Steamin’. These 1950s albums were fast paced jazz albums that were densely packed with music, chord changes and feverish solos. It was after Coltrane’s departure from the band and Davis’ three-year sabbatical from 1960-1963, that these two artists would explore a looser sound in their playing.

Coltrane focussed on his solo career upon his departure from Davis’ sextet (The first classic quintet had evolved into a sextet) in 1960 and recorded My Favorite Things. The title track from this album, which was taken from the popular Broadway production The Sounds Of Music, was relatively tame compared to his later compositions, but offered a view of what lay ahead. In the album’s title track, Coltrane displayed his ability to take a standard mainstream tune and give it energy and vibrancy through his own soloing technique. As a debut album, My Favorite Things basically alerted the jazz world and it was an appropriate overture to Coltrane’s work over the next seven years. This tune would become a staple in Coltrane’s sets right up ‘til his death.

Throughout his short but prolific playing career, Coltrane explored numerous avenues of music. After his brief stint with Atlantic Records, Coltrane made his move over to Impulse Records, where he would produce some of his most blistering compositions and solos. During his time with Impulse Records, Coltrane touched upon European classical music, American spiritual hymns, and Eastern music improvisational techniques. Coltrane was a consummate innovator, who was constantly evolving his styles. From 1961 to 1965, his music with his classic quartet of McCoy Tyner, Elvin Jones and Jimmy Garrison was considered his best years. This quartet did not occur overnight as Coltrane went through many incarnations until her found the right musical formula. Throughout these years, saxophonist Eric Dolphy, drummer Roy Haynes and bassist Reggie Workman frequently played with Coltrane but never were considered full time members. What Coltrane found advantageous in his quartet was the subtle accompaniments of Tyner and Garrison and the frenzied and aggressive drumming of the constantly sweating and smiling Jones. The music during these years was slightly evolved from the hard bop that he played with Miles Davis and was steadily developing towards the anarchic sounds of his free jazz from 1965-1967.

During his first three years with his classic quartet, Coltrane released Africa/Brass, Coltrane, Ballads, and Impressions. Ballads represents the smooth side of Coltrane, somewhat reminiscent of his work with Davis and Thelonious Monk and on his self-titled album, Coltrane paid homage to his former leader, Miles Davis, with the composition "Miles Mode". Africa/Brass was a rare session that featured a full sized ensemble backing Coltrane and provided early hints of African spiritualism that would typify Coltrane.

Throughout these early albums, Coltrane also re-introduced the soprano saxophone, which was used in Dixieland bands during the first half of the 20th Century and popularized by the great Sidney Bechet. Coltrane integrated the soprano saxophone, with its distinctive Oboe-like voice, back into the jazz mainstream. Although these studio albums were well crafted, it was Coltrane’s live recordings such as Live at the Village Vanguard and Live at Birdland really displayed the qualities of the lineup. With the reliable rhythm section, Coltrane would often blow 45- minute solos during his live shows and virtually blow the minds of every fan, player and critic. This Coltrane characteristic was best heard through the tune "Chasin’ the Trane". This tune, which lacked any formalized structure, was an avenue for Coltrane’s harmonic explorations and served as a musical launching pad similar to the Grateful Dead’s Dark Star, the Allman Brother’s Mountain Jam or Phish’s Mike’s Song.

While Miles Davis went on a three-year sabbatical from 1960-3 and John Coltrane was taking his "Giant Steps" as a leader, a pianist by the name of Herbie Hancock entered the New York jazz scene. Born and raised in Chicago, Hancock came to the Big Apple as a sideman with trumpeter Donald Byrd’s band. It was through Byrd, that Hancock and Miles Davis were to first meet.

Upon his arrival in NYC, Hancock became a wanted man and was immediately recruited by the Blue Note label to record as a leader. His first album for Blue Note was the appropriately titled Takin’ Off. The undoubtably highlight of the recording session was the tune "Watermelon Man". Although this be-bop version was truly remarkable and a huge hit at the time of its release, it would be his funky re-make of the tune 12 years later that would give the songs its widespread appreciation. Even in the 1990s, that tune continue to ensnare new jazz listeners.

Throughout his early albums with Blue Note, Hancock established himself as an adept soloist and incredible composer. It was these attributes that brought Hancock and Miles Davis together in 1963. By the close of 1964, Miles Davis had also recruited Wayne Shorter, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams. This was to be the lineup known as Davis’ Second Great Quintet . Over the next four years, the quintet recorded E.S.P., Sorcerer, Nefertiti, Miles Smiles and Miles In The Sky. These albums were all very similar in musical approach as the quintet developed a sound niche somewhere between the bebop/modal sounds of Davis’ late 1950s albums and the avant-garde of Ornette Coleman. This new sound was familiarly referred to as freebop.

An interesting aspect of these albums was the decentralization of Miles Davis. By the time 1965, Davis had already become a living legend. His work in the 1940s and the "Birth of the Cool" as well as 1960s’ Kind of Blue had lifted Davis to the level of jazz genius. During the albums with the quintet, the emphasis was placed on the band as an ensemble. Of course, there are amazing solos throughout these recordings, but the majority of the tunes were written by Shorter and Hancock and the band focussed on creating a unified sound. In his autobiography, Miles Davis spoke of the lineup and its cohesiveness: " I knew that Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams were great musicians, and that they would work great as a group, as a musical unit. To have a great band requires sacrifice and compromise from everyone; without it, nothing happens."

The de-emphasis of Davis was exemplified on 1967’s Sorcerer, which was completely devoid of a Davis composition. It was Davis’ well placed trumpet bursts, Shorter’s melodic weaving, William’s polyrhythmic drum beats, Hancock’s skillful accompaniment and Carter’s reliable walking bass lines that brought this quintet together as one well organized playing unit. One of compositional highlight’s from these albums was Wayne Shorter’s "Footprints" which was recorded on 1966’s Miles Smiles. Since its first release, "Footprints" has turned into a jazz standard and has been preformed by a vast number of musicians including classic jazz artists such as Lee Konitz, free jazz pioneers like Pat Martino, and modern hip-hoppers like Liquid Soul.

Like Elvin Jones in Coltrane’s quartet, Tony Williams was the driving force behind the Miles Davis Quintet. Both Jones and Williams were adept at playing poly-rhythmically and driving the music from underneath. These two drummers were primarily responsible for the development of the free-jazz drum style as these two drummers had a less of a traditional timekeeping role and more of an active participant role. In the cases of both Coltrane’s and Davis’ bands, the band’s dynamics were based on the drummers and soloist’s passionate and vigorous interplay, while the pianists and bassists diligently kept the music grounded and on track.

Tony Williams maintained the same youthful enthusiasm and passionate drumming technique outside of Miles Davis’ band as well. On many instances, Williams would join Herbie Hancock for his solo work as well. Throughout his tenure with Davis, Hancock continued to produce magnificent solo efforts for Blue Note Records. During this period, Hancock recorded Empyrean Islands, Maiden Voyage and Speak Like A Child. For 1965’s Maiden Voyage, Hancock kept together the Miles Davis rhythm section as he brought in Carter and Williams. The session also featured George Coleman ( who was Wayne Shorter’s predecessor in the Miles Davis band) and Freddie Hubbard. An interesting take from the Maiden Voyage was Hancock’s "Little One". This tune was featured on Davis’ E.S.P. as well as Maiden Voyage. As for the title track, the tune is based on the coda or final melody statement of the Ron Carter’s "Eighty-One" which can also be found on E.S.P. These two tracks exemplify the interchangeability of sounds and musicians during this period of jazz. On Empyrean Islands, Hancock released "Cantaloupe Island", with its incredibly catchy rhythm, would be re-popularized through US-3’s "Cantaloop (Flip Fantasia)" which dominated the airwaves in 1994.

The creative spark for both Herbie Hancock and The Miles Davis Quintet were the years 1964 –1965. During this era, the Quintet’s E.S.P. and legendary Live At Plugged Nickel concerts were released on Columbia while Hancock recorded albums like Maiden Voyage for Blue Note. During this great interaction of musicians and recording sessions in the Blue Note and Columbia studios, John Coltrane was still pursuing his own musical vision. From 1964-1965, Coltrane recorded albums such as Crescent, Sun Ship, Infinity and A Love Supreme. The latter was Coltrane’s landmark album. It possessed all the elements that characterized Coltrane: beautiful solos, solid yet innovative accompaniment, a touch of religious spiritualism and experiments with the music of the Far East. A Love Supreme made a rock and roll crossover with an album by guitarists Carlos Santana and John McGlauglin called Love, Devotion Surrender. The album, which is dedicated to the spiritual leader Sri Chimnoy, begins with an outstanding electrified version of the first suite on A Love Supreme. With Carlos Santana, who was known to wear Coltrane T-shirts on stage, recording Coltrane’s tunes in a rock format, it is evident that Coltrane penetrated all types of music. This is further exemplified by various music teachers transcribing Coltrane’s solos in order to teach classical music techniques.

In the liner notes to the similarly spiritual album, Crescent, Coltrane discussed his view on his music: "The main thing a musician would like to do is to give a picture to the listener of the many wonderful things he knows of and senses in the universe." In addition to his prolific recordings, these two years were extremely special, as his sons John, Jr. and Ravi were born on August 26, 1964 and August 6, 1965, respectively. Ravi was named after the great sitar player Ravi Shankar who served as both a musical and spiritual advisor for Coltrane during the latter stages of his life.

By the end of 1965, Coltrane had developed his music beyond the limits of his quartet. For their final album as a single cohesive unit, Sun Ship, the classic quartet began to show signs of musical disparity. As Coltrane pushed his soloing technique into free jazz, the remaining members did not share the same musical foresight. Coltrane’s searches for the avant-garde during the Sun Ship sessions served as a catalyst for change. In the same year, Coltrane took the quartet into the studio for the recording of Meditations where they were joined by saxophonist Pharoah Sanders and drummer Rashied Ali. This session would signify the gradual transfer of power from the hard bop of the classic quartet to the free jazz that characterized the last two years of Coltrane’s life. Compared to his earlier albums, where the composition ranged from 4-9 minutes, Meditations had two extended suites, which averaged twenty minutes in length. Although his music on Mediations and Ascensions was strikingly different, Coltrane’s compositions still possessed the same zeal of his previous work. Coltrane’s last few albums with Impulse were a stark contrast from his recordings with Tyner, Garrison and and Jones, yet they still managed to capture the ears of jazz America with Coltrane’s impassioned performances.

Coltrane’s worldview went far beyond simply making music. He felt that he was a spiritual preacher and his music was the sermon. Coltrane discussed this approach in the liner notes for Meditations: "My goal in meditating on this through music, however, remains the same. And that is to uplift people, as much as I can. To inspire them to realize more and more of their capacities for living meaningful lives. Because there certainly is meaning to life." Unfortunately, the world lost a great player and source of inspiration during the summer of 1967. Long before our culture witnessed the deaths of great young musical proteges such as Joplin, Hendrix and Morrison; we lost Coltrane.

Although the death of Coltrane was a tremendous loss on the jazz environs, musical creativity kept on pushing forward during the second half of the 1960s. The Miles Davis Quintet’s Nefertiti (1967) symbolized the last time that the quintet would record together acoustically. It was also another Miles Davis album in which he contributed no songs. Although it was "The Miles Davis Quintet", the band worked together to create a melodic unified sound where the emphasis was on subtle harmonic changes rather than examples of individual virtuosity. It is through the first two Shorter compositions, Nefertiti and Fall; it’s easy to ascertain the chemistry between Miles Davis and Wayne Shorter. Just as Davis maintained a melancholy tone to his playing style, Shorter’s compositions were also dark and haunting. By 1968’s Miles In The Sky, Davis took his first steps towards the electric sounds late 1960s-early 1970s. This was signified by the guest electric guitar playing of George Benson and Hancock’s earliest use of the electric piano. Within two years time, the Quintet would be completely dissolved and Davis was playing his trumpet with an electrified wah-wah pedal.

By the time Herbie Hancock left the Miles Davis Quintet, his fame had reached new limits and appealing contracts had drawn him away from Blue Note and off to Warner Brothers. With the switch of labels, there was also a transformation of his sound. As Hancock entered the 1970s, his work blended from the fusion of Mwandishi into the funk of the Headhunters. Before his departure from Blue Note, Hancock recorded one last classic album, 1969’s The Prisoner, which featured a larger ensemble and beautiful Hancock originals.

The one thing that needs to be remembered about these artists is their roots. Each of these musicians created huge impacts on the jazz world. From their earliest recordings up to their last or latest, Coltrane, Davis and Hancock were always pushing the musical envelop.

In many cases, these artists are best known for their extreme work. Coltrane will always be remembered for his final albums where he took the free-jazz sound and stretched it further; Miles Davis will always be remembered for his jazz rock fusion from 1968 – 1974 and Herbie Hancock is synonymous with the jazz-funk explosion of the mid 1970s. The new re-releases and compilations of the 1990s remind us that these musicians had their roots. Listening to Hancock, we revisit his ethereal compositions and see beyond the funky beats of Headhunters or the danceable electronica of 1984’s "Rockit". Through Miles Davis’ mid 1960s releases, we witness his constant style development, in which Davis borrowed elements from be-bop, fusion and the avant-garde to create his own unique sound. In Coltrane, there was the spirituality and mysticism that was responsible for enthralling thousands of listeners. In all of these releases, there is the constant of thoughtful, introspective compositions. During this period, soul-jazz and the organs of Jimmy Smith, Jack McDuff and Jimmy McGriff were the popular grooving sounds and the world was on the eve of the releases of The Doors, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Surrealistic Pillow. These releases represent the last bastions of acoustic jazz before jazz was to go electric and rock and roll was to reign supreme.