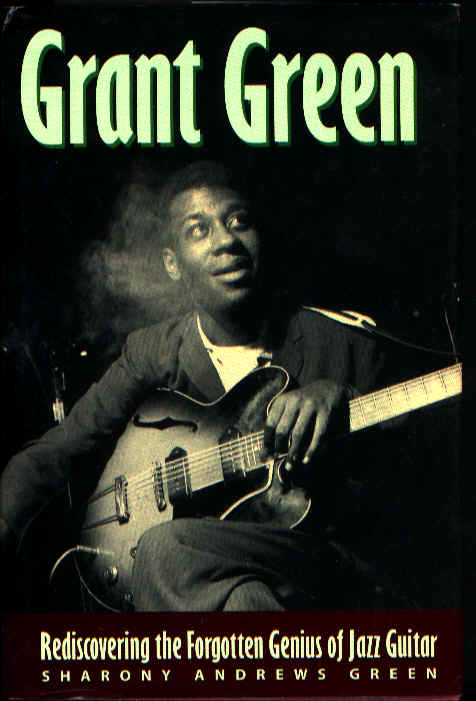

Book Review: h3>Grant Green – Rediscovering the Forgotten Genius of Jazz Guitar (Miller Freeman Books: Sharony Andrews Green)

By Brian L. Knight

Guitarist Grant Green holds a unique position in jazz history. He was one of Blue Note Record’s most prolific recording artists. He received the utmost respect and admiration of his peers, critics and friends and his music of the 1960s and 1970s has made a lasting impact through 1990s hip-hop samplings. Despite these triumphs and accolades, Green still holds the indistinct honor of being relatively unknown and unheralded. When the word jazz guitar is mentioned in mainstream circles, the names Wes Montgomery, John McGlauglin, George Benson, Kenny Burrell and Pat Metheny come to mind, but never Grant Green. To some degree, jazz guitarists are left out of the limelight. In addition to Grant Green, there is also Jim Hall, Tal Farlow, Barney Kessel, Joe Pass, Eric Gale and Hugh McCracken who also remain relatively unknown. While the jazz world seems to emulate the trumpeters, saxophonists, pianists and drummers; the concept of the "guitar god" belongs more to the rock and roll sphere and less with jazz.

It is the goal of author Sharony Andrew Green to reverse Grant Green’s sleight of honor. Although featured on countless acid jazz compilations in the 1990s, the legacy of Grant Green and especially, the man behind the music has remained a mystery since his death in 1979. Sharony Andrews Green, who has been a journalist for both the Miami Herald and Detroit Free Press, provides an in depth look at the short but brilliant career of Grant Green. Sharony Green provides a view of Grant Green that is remarkably different from other jazz biographies. For one, she had an inside track as she was married to Grant Green’s youngest son, Grant Green Jr. Through family recollections, Sharony Green offers a fresh approach to a jazz biography. Second, Sharony Green is not a jazz critic. She is less concerned on Grant Green’s mastery of the guitar pick or his unique use of octaves, and more focussed on the man himself and the life that he lived.

The fact that Sharony Green is related to the Green legacy would make one believe that the book is full of in-depth details and wonderful anecdotes. In reality, her intimacy with Green family simply extrapolates the personality /lifestyle faults of Grant Green. Instead of being told stories of family picnics etc; the Green family can only provide stories of a father who was never around; a father who had a drug problem and person who was a father in a multiple families. The greatest display of the Green mystery comes at the end of the book when the author discusses Grant Green’s funeral. Sharony Green couldn’t find a precise tale about the ceremony. Some tales relayed stories of a militant Muslim takeover while others relayed a story of three different wives rising when the preacher asked "Will the wife of the deceased please stand." Even during a highly emotional and personal event such as a funeral, the Grant Green enigma continued on. Just as much as Grant Green remained a mystery to the music world, he was equally a mystery to his own family.

On the musical side of things, the author is quick to point out that Grant Green received his greatest accolades with his early collaborations with the Hammond B-3 organ in trios or his later work during the early 1970s, when Grant Green earned his moniker of "The Father of acid Jazz." Both of these distinct phases had Grant Green experimenting with R&B and soul’s influence on the jazz idiom. Either through the slinky sounds of the Hammond B-3 or his more danceable tunes such as 1970s’ "Sookie Sookie", Grant Green masterfully combined elements of funk, jazz, gospel, blues and R&B. What is often forgotten and the author reminds the reader, is that Grant Green was also a master at straightforward be-bop jazz. During the early 1960s, Grant Green recorded over 100 albums with Blue Note as either a leader or sideman. Although many of these recordings were on the funky side of things, a vast amount remained true to modern jazz. One such recording was 1963’s Idle Moments which has been recently re-released as part of Blue Note’s Rudy Van Gelder Series. In contrast to Grant Green’s more popular trio recordings such as Green Street (1961), Grant’s First Stand (1961) and Iron City (1967) or his acid jazz classics such as Carryin’ On (1969), Alive (1970) or Live at the Lighthouse(1972), Idle Moments features a sextet consisting of Joe Henderson (tenor sax), Bobby Hutcherson (vibes), Duke Pearson(piano), Bob Cranshaw(bass) and Al Harewood(drums). Especially with the presence of Hutcherson’s ethereal vibes and Pearson’s non-Hammond ivory playing, this album provides a whole different glimpse at a somewhat narrowed vision of Grant Green.

Although the Rudy Van Gelder re-master of Idle Moments was a divergence from the atypical Grant Green sound, Sharony Andrews Green considered that Green and Van Gelder were the perfect combination for creating the "Blue Note Sound." The author explains the "sound": "It is at once funky, jazzy, soulful and other adjectives that mean little until one actually hears the music. It can make you dance. It can make you cry. It is cogent and it is hard to miss. It is what made Alfred’s (Alfred Lion – Blue Note founder) foot start tapping in Rudy’s studio when the cats who gathered to play were on the right track."

The previous description, although laymen in approach, is very accurate. It is through this void of technical lingo that Sharony Andrews Green is able to attack the story of Grant Green with youthful innocence. Coupled with the fact that the man was a mystery to both family and friends, Sharony Green’s fact-finding technique was both innovative and unorthodox. Instead of simply talking with countless Green’s fellow musicians (just about anybody who recorded at Blue Note in the 1960s), Sharony Green holds interviews with old elementary school friends, fellow devout Muslims, his more obscure associative musicians and old nightclub owners. Sharony Green’s na´ve innocence to the jazz idiom provides a smooth untechnical/un-jargon filled read. At the same time, there is a need to satisfy the music fans as well. Although a successful attempt at revealing the man behind the music, it would have been nice to hear more from his musical contemporaries. For instance, it would have been better to hear Rudy Van Gelder’s recollections of Grant Green rather than to hear the stories of Ruth Brown, the Blue Note secretary during the 1960s. The naivete of this book is further exemplified with the presence of 19-year-old Swiss fan, Tobias Jundt, who wrote the 31/2 page technical section and the selected discography reviews. Jundt’s knowledge of Green’s work and technique is remarkable and it is refreshing to hear a young man’s take on a subject that is traditionally dominated by older, more learned generations. At the same time, as the book becomes the premier source on Grant Green, there is a need for a more credible authority.

Sharony Andrews Green clearly overcame information gathering adversity to write this book and it is great to read about Grant Green outside the limitations of a liner note. It is the content of these liner notes that Sharony Green obviously wanted to avoid. Jazz critics such as Gary Giddins, Leonard Feather and Nat Hentoff have provided the technical/musical story behind Grant Green, while Sharony Green searches for the personality traits. Despite her intimacy with the family, countless interviews and her innocence to jazz, there is still something missing from the book. Fortunately for Sharony Andrews Green, the missing element was not as much as her research methodology or writing technique, but Grant Green himself.